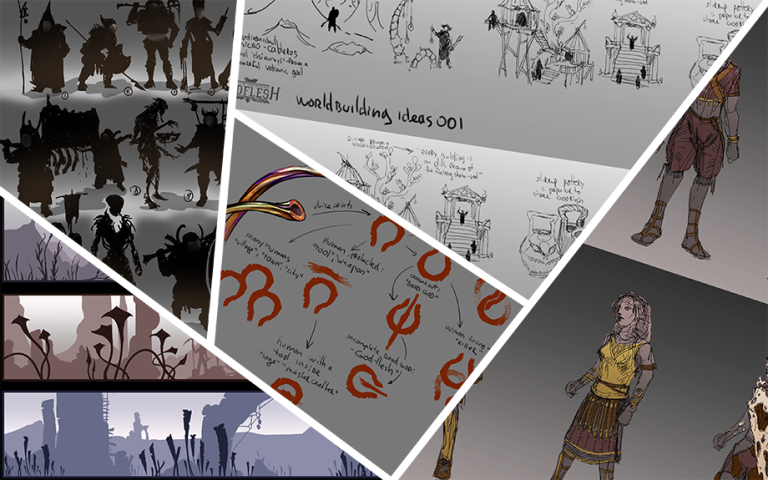

After months of playtesting and refining the rules for Godflesh, we reached the point where we needed to translate this world into something visual. That meant bringing in Mikhail Malkin as our lead artist for a series of visual development sessions starting in early September.

Mikhail is an active member of the UK TIN community, a London-based multidisciplinary artist who combines traditional and digital illustration, concept art, 3D modelling, and an unquenchable love of worldbuilding and history in his work. He’s been a TTRPG player for over two decades. He is a published game designer in his own right, which means he always looks at the task at hand from both the perspectives of a Game Master and a player to find practical applications for whimsical visuals, aiming to make the game fun and the story memorable.

Finding the Tone

The first challenge was ensuring we were aligned on what kind of world this is. Godflesh operates in a specific space – Bronze Age technology saturated with divine influence. Gods aren’t benevolent protectors – they’re grotesque, monstrous entities whose presence warps reality. The world exists in constant tension between ordered domains, where gods rule, and chaotic wildlands left behind when those gods fall.

We discussed the distinction between the Strain – subtle divine markings that allow for character variety – and full godflesh consumption, which results in monstrous transformation. This balance was crucial – we wanted supernatural influence whilst keeping characters fundamentally human.

Early explorations focused on how divine influence might manifest visually, particularly through plant-based markings and environmental corruption. These concepts extended throughout the world’s visual language.

Characters and Human Diversity

The character work focused on establishing range whilst maintaining consistency. The silhouettes show warriors, travellers, merchants, and those touched by divine influence in various ways. Everything adhered to Bronze Age constraints – spears and shields rather than massive swords, equipment reflecting pre-iron age technology, but with enough supernatural elements to make the world distinct.

The goal was to show that human diversity in Godflesh comes from divine influence rather than separate fantasy species. Everyone remains recognisably human despite unusual features or divine touches. You can see this in body shapes, unusual features, and equipment choices, all showing the Strain’s influence without abandoning human form.

The character clothing explorations showed how people dress in ordered domains versus wildlands. Bronze, bone, leather, and godflesh remained the primary materials across all designs. The wildlander designs incorporated bone or godflesh elements more prominently, suggesting someone who’s spent significant time in dangerous territories and adapted accordingly. The ordered domain designs showed more refined craftsmanship, suggesting access to better resources and stable working conditions.

This work highlighted an important point about contemporary interpretation. The designs needed to feel Bronze Age in their materials and construction, whilst avoiding the trap of looking generically ancient. We wanted outfits that felt specific to this world, that showed divine influence in textile choices and ornamentation, that balanced historical grounding with supernatural elements.

Environments and Atmosphere

Landscape work began with silhouette studies exploring what wildlands look like, how divine influence manifests in plant life, and how to create ambiguity between natural formations and divine architecture. Some explorations focused on alien vegetation patterns, while others concentrated on structures that might be ruins or something that was once alive.

That ambiguity is intentional – in Godflesh, the line between natural and supernatural is constantly blurred. The vegetation doesn’t follow natural patterns entirely. Structures might be built or might be petrified remains. This uncertainty creates an atmosphere whilst also serving practical worldbuilding purposes.

Communication Without Literacy

Developing a visual language for a world where literacy is forbidden proved particularly challenging. The symbol systems we explored could convey meaning without crossing into actual language – marks that might be carved, painted, or woven to communicate information about gods, godflesh, transformation, and divine power.

The plant-based design approach worked particularly well, suggesting something organic rather than constructed language. Each symbol represents different states: ordinary plant life, anti-human divine entities, incomplete remains of dead gods, humans living alongside divine power, humans who’ve fused with divine power, and various permutations between these states.

Resources and Economy

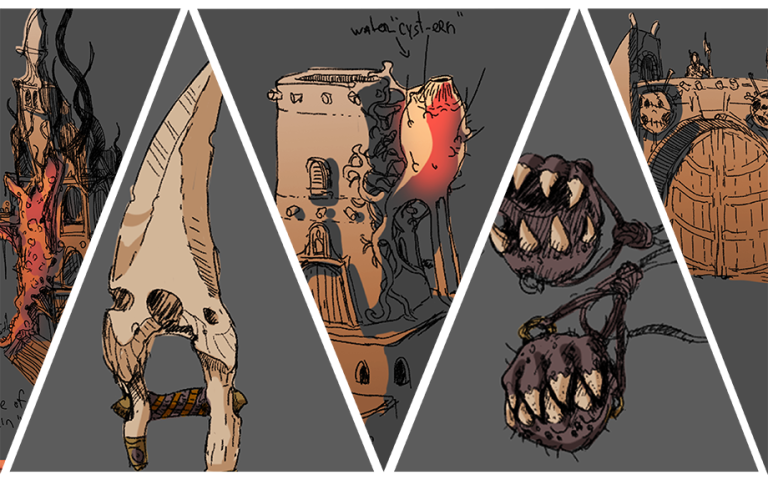

A crucial realisation emerged about godflesh as a resource. We’d been focused on godflesh as a source of transformation – consuming specific organs to gain power. But hunters pursue hearts, brains, and livers whilst discarding most of the remains. What happens to all that waste?

The answer became central to understanding the world’s economy. Discarded godflesh becomes construction material, gets repurposed as biological mechanisms, and creates wild growths across the landscape. This creates “fleshy landscapes” – areas bearing visible scars from divine battles where otherworldly corruption has literally reshaped reality. It’s environmental storytelling that shows where significant events occurred whilst also serving as economically valuable resource sites.

This reframing changed how we think about the setting fundamentally. Divine remains aren’t just magical power sources – they’re practical materials that make civilisation possible in this dangerous world.

Architecture and Cultural Identity

The architecture explorations revealed that different regions and communities would develop distinct visual languages. Civil architecture drew from North African mud-brick traditions but incorporated setting-specific elements. Ancient customs influenced designs – some buildings have no ground-floor doors, reflecting historical security practices. Guard-stones displaying loyalty to ruling gods create interesting secondary effects when gods fall – all those discarded carved idols have to go somewhere.

Some work explored divine corruption directly, showing structures in their intended form alongside what happens when organic growth takes hold. This visual contrast demonstrates the central tension of the setting – human civilisation existing precariously, always vulnerable to divine influence.

The sacred architecture explorations pushed into the structures that define ordered domains. Three distinct architectural styles emerged, each with its own cultural logic. One drew inspiration directly from divine forms, translating physical characteristics of a long-dead god into vertical architectural elements. Another focused on combining protective exteriors with spacious interiors, displaying both divine and human symbols to express the concept of inheritance. The third came from a practical discovery – mixing blood from slain monsters with traditional building materials to create new substances with unexpected properties.

What made this work compelling was the balance between divine influence and human ingenuity. These structures are larger and more imposing than Bronze Age technology alone might suggest, but they’re still built by human hands using materials that fit the world’s constraints. The silhouette explorations emphasised scale and presence, including human figures to show just how massive these structures are.

Equipment and Survival

The weapon explorations centred on a fundamental question: how do you fight in a world where some enemies are mortal and others are supernatural? We explored the distinction between bronze weapons for dealing with ordinary threats and godbone or godflesh-augmented weapons for supernatural creatures.

The material constraints remained consistent – Bronze Age technology as the baseline. But divine remains offer possibilities beyond what natural materials allow. Bones that hold their edge better than any bronze blade. Organic components that maintain some vestige of the creature they came from. Some explorations pushed into truly alien territory – weapons incorporating living godflesh components, organic elements that might have limited lifespans, materials that require careful handling.

These aren’t just aesthetically different – they have practical implications for how adventurers plan and execute their journeys into the wildlands. The distinction between weapons for mortal versus supernatural threats isn’t just mechanical – it’s cultural, economic, and practical.

Crafting and Risk

An intriguing parallel emerged to historical tanning processes, where craftspeople used brain matter and other organic materials to properly cure hides. In Godflesh, blood and bile from slain gods, dragons, or other supernatural creatures could provide the plasticity needed to craft or infuse items with divine properties.

This introduced a compelling tension: working with godflesh is time-sensitive. The more complex the piece you’re attempting, the greater the risk of ruining your materials. There’s a race against corruption, decay, or simply the hazardous nature of divine remains. This affects how characters approach crafting and how communities organise expeditions.

The non-offensive equipment explorations showed other applications. Containers fashioned from supernatural organs. Protective gear incorporating composite materials. Items with limited shelf lives that must be used before they degrade or become dangerous. Each concept reinforced that godflesh is valuable but volatile.

The Foundation

These first four weeks established the visual foundation for Godflesh. We moved from broad tone-setting to specific practical details, answering questions about how people survive, what they build, what they carry, and how divine influence manifests at every level of the world.

The architectural work showed that different regions have distinct identities, with divine influence creating variety rather than uniformity as different cultures interpret and adapt to supernatural forces in their own ways. Equipment tells survival stories. Materials drive the economy and culture. Every visual element reinforces the world’s fundamental dynamic – humans living in a reality shaped by forces vastly more powerful than themselves, finding ways to persist, adapt, and even exploit those forces.

Visual development continues, but we now have a solid foundation to build on – a world that feels consistent, dangerous, and uniquely its own.